- (The three German words that distinguish different types of knowledge)

This article was extracted from one I wrote for Gift of Fire, issue 133, 46-47 (November 2002).

There is more to knowledge than a vague familiarity, or lexicographical and grammatical skills required in deciphering facts, all of which three-year-old prodigies and idiot savants are sometimes capable. Full knowledge is not a memorized taxonomy; it requires ‘hands on’ experience in evaluating conjectures and testing them for oneself – not all the conjectures that constitute what is known, to be sure, but the ones that experienced intuition leads one to doubt in particular. This does not mean that one must build their own cyclotron in their basement or travel to drop cannon balls and feathers from the leaning tower of Pisa any more than Galileo did, but one must understand why and how one might, should those tests seem necessary. Without this intuition based on experience that makes of the acquisition of knowledge a creative personal adventure, one can not truly be said to “know” anything at all.

Of course many ideas – including some we consider epistemological – are mere hand-me-down memes with no validity of any sort other than their own survival value. And such memes do fight like rabid dogs, whether they are valid or invalid. That there may be some however dubious merit in ideational longevity need not be contested here, but that Truth is definitely something else should be obvious. So if what we hold as knowledge (or precursors of Truth) is to claim more than mere lineage or tradition as its source of legitimacy, it must be we ourselves who at all times ennoble such conjectures. Whether reincarnation or relativity, by authorizing tests whereby our own or other’s conjectures may be refuted, we do them great honor in bringing to life the process whereby they become worthy of consideration as Truth. The ‘authorization’ is the open mind we bring to the possibility of refutation; without such permission, no conjecture can be elevated above that stature. Nor do we truly own any other knowledge. As Abraham would offer up his well-beloved son to God in sacrifice in Judaic myth, so must we offer up our precious offerings to test. And if perchance an alternative should be put forward that withstands the designated tests, then Truth depends on our willingness to switch loyalties. At each step we must demonstrate that same robust willingness to smash our most precious diamond knowing that if it is the real thing it will survive.

And importantly, we must be willing to discuss alternatives, to debate them, to attack them. We can demand nothing less of what we know!

Popper’s Conjectures and Refutations provides much in the way of philosophical motivation for these arguments, and perhaps they could have been couched more as a review than a personal testimony. But I have chosen to take the latter approach because what I have to say here is not a review of someone else’s opinions and research, but of my own that happens – I find upon reading Popper’s excellent work – to correspond in many ways with his. And this is the aspect for which I ask your indulgence. That this sense of what we know can in some however small way be considered personal and our own is what is important to us both as individuals and in whatever professional capacity we may happen to earn a living. It is of no real significance in this regard that one may happen to possess a sheet of paper in a drawer somewhere indicating that one holds a Ph.D. in physics, chemistry, or neurology from a prestigious institution such as Oxford, Stanford, MIT, or Harvard, but as an ungraduated student of nature in its fullest sense of seeking to know what this universe is all about. So if I have to have credentials beyond a B.S. in physics and graduate level courses taken some forty odd years ago to impress you, you may as well quit reading; this is already way over your head. That one can acquire knowledge by effort and intelligence alone to rival that exhibited in articles of refereed journals is a transcendental relic of reformation that I hold dear. If you will grant this possibility, then perhaps you will not have too much difficulty with the related notion of knowledge being in some sense only what we individually have come to accept as unrefuted conjecture based on our own demanding tests of its validity.

Knowledge as surviving hypotheses after extensive testing in a sincere attempt to ruthlessly refute conjectured truths as against pretending to confirm them – an effort requiring insight into all future developments in science, for example – is a worthwhile concept. It is not always easy to see the distinction between not having refuted, and having confirmed a theory, and certainly after many valiant attempts at refutation, one can easily slip into a comfortable mode of believing that mere conjectures have been confirmed as Truths of nature. Subsequent developments may, however, suggest that certain previously unquestioned assumptions are nonetheless invalid, in which case implications with regard to possible refutations of ‘confirmed’ conjectures may need to be re-tested. Later developments frequently involve bold hypotheses with regard to pallid notions that had formerly remained unquestioned. For these reasons it is important that the structure of underlying assumptions of any accepted theory be understood so as to maintain validity of the tests for refutation that alone provide integrity to the flux of advancing contenders to the status of ‘Truth’ writ large. Therefore, without understanding the structure of what we ‘know’, we do not know. Because useful knowledge must always involve a readiness to test formerly accepted dogma.

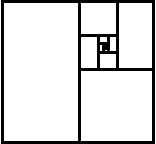

So is that murkiness all there is to Truth? Not entirely; but it does indicate how scientific Truth must be sought as a prescription to be followed if we are ever to realize what might be considered to approximate universal Truths. I think in the grandest sense that meaningful assaults on Truth can be mounted such that a level of understanding more closely approaching that denomination than preceding ones that did not survive the barrage of discriminating tests can be attained in the same sense that we know that the sum from n equal one to infinity of (½) n equals unity, exactly, even though all the individual steps of this summation could never be completed. And although conjectures may fall like waves of favorite sons – devoted soldiers on a battlefield, none of which could ever have achieved the victory by itself any more than one standing pawn could ever claim victory in chess, each – even in defeat – contributes to that relentless crusade for Truth nonetheless.

In comparison to this participatory approach to knowledge, encyclopedic knowledge – book larnin’, if you will – is just a stroll though dusty archives of the dead past in a museum providing cartoon depictions of former epistemological battles. Here are interred only the names and artifacts of the survivors and most notable of the fallen dead with but a few puerile re-enactments of the most famous battles on display. But these surely do not convey the ways in which the banners furled and fluttered in the ebb and flow of great events – the “Oh what might have beens.” Such unimpassioned depictions are the mummification of knowledge, lifeless yellowing snapshots and tired text concerning the ‘good old days’ of glory, however recent, however gory. ‘Science’ on the other hand defines knowledge actively as results obtained by participation involving exhaustive experimentation, if only in the mind, as the rite of passage. ‘Knowing’ by having tested in the sense of ignis aurum probat. There really is no other way.

Leave a Reply