Idioms don’t tend to address sensitivities. I should note that I have nothing against cats, having owned a few, although I prefer dogs. I am certainly no expert at, or sympathetic with, removing their pelts.

That said, the particular idiom to which I refer is: “There are more ways than one to skin a cat.” This is not a Schrödinger’s Cat joke, by the way. No, I’m serious… but in a different way. And, however grotesque, it gets across the notion that in virtually every endeavor there are more ways than one at effecting a desired result. While at the same time seeming to deny the ideal situation of the existence of an ‘only’ or a single ‘best’ solution to any problem.

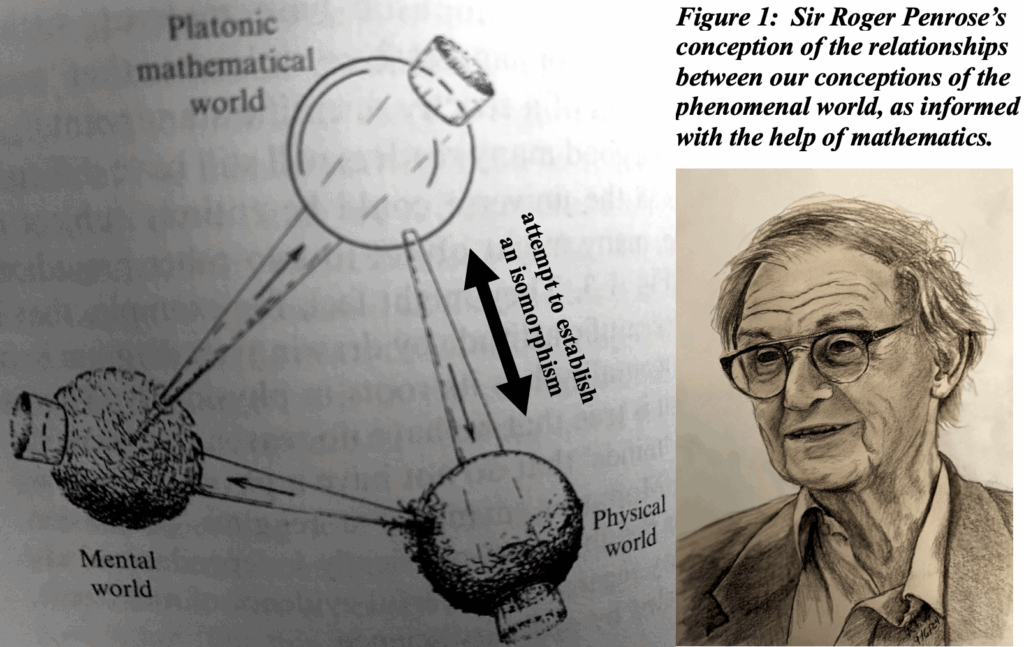

The scientific method attempts to come up with isomorphisms between reality and mathematical formulas more or less as one might make a shorthand (mathematical) description of a complex situation. The ideal is that this mathematical description or model would be isomorphic to the reality, but in actual fact there typically is no perfect match. It is Plato’s cave problem in reverse where, rather than real objects that conform imperfectly to the ideal as in a ‘spherical’ earth and tennis balls are not perfectly spherical. Science formulates ideal mathematical descriptions to capture physical phenomena – but only as closely as possible. As Roger Penrose expressed it in his The Road To Reality, Plato “envisaged that these ideal entities inhabited a different world, distinct from the physical world. Today we might refer to this world as the Platonic world of mathematical forms.”

This leads to several problems: We tend to fall in love with mathematical formulations just as Plato fell more in love with his idyllic realm than with actual reality. The real world is where a scientist’s affections must be focused – not his formulas or an ‘image in a mirror.’ So we have the following,

1) The scientific method seeks isomorphisms between reality and mathematics.

2) But often what we actually get is a many-to-one correspondence, not strict isomorphisms. This situation is not illustrated in Penrose’s conception illustrated above. There may be several mathematically distinct structures that can each provide an adequate, even elegant, description of the same observed behavior.

Therefore, the mapping from mathematics to physical realities is frequently non-invertible, in which two separate formulations may account for the same phenomena. There are notable situations where this has occurred such as Schrödinger’s wave mechanics and Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics. They seem compatible, so I guess that comes down to who cares? (I think in this case it was both Erwin Schrodinger and Werner Heisenberg who cared.) Although with Einstein’s reformulation of gravity, there seems to be a consensus that Newton was wrong – but not by much, if any, in most cases.

In thermodynamics there is the ‘ideal’ gas law that doesn’t precisely apply to all thermodynamic systems. It only applies to systems in equilibrium, whose pressure, density, and temperature are unchanging. That is almost never the case. But since a system that is not in equilibrium always strives to get there, the formula provides the basis for analyzing perturbations.

There is also the situation of mathematical formulations of physical phenomena being altered because of what are considered more elegant (or in vogue) mathematical expressions of the same concepts as in converting vector formulations into tensor expressions, etc.

In the search for ‘truth,’ which is the problem Plato and Penrose addressed, what criteria should we apply in this particular mental game? An isomorphism, to the extent that it addresses the full scope of the observed phenomena probably has a legitimate claim to such a lofty goal. But are there any such complete isomorphisms? And what level of ‘Truth’ should we grant incomplete relationships?

It isn’t clear what distinction Penrose would give to ‘physical’ and ‘metaphysical’ realities In his initial discovery that Lorentz contraction could never be observed, he nonetheless accepted that contraction is a reality in some sense in as much as there is another transformation, besides the Lorentz transformation, that can be applied to the results of the latter to obtain the appearance of the ‘physically observed’ world. To my mind, a metaphysical world exists only in the Platonic domain of mathematics and is dispensable if we limit ourselves to what can be observed.

This brings us to what we understand the innerworkings of that idealized bubble at the top of Penrose’s diagram to involve. As a black box (white in this case), it takes as input a human question and generates as output an explanation of why the physical world behaves the way it does. As an opaque magic geode it could be filled with scientific logic or religious nonsense. It is by virtue of transparency that we are enabled to examine the logical quality of the explanations it gives.

Whether logic itself belongs in the mathematical bubble or the mental world can be disputed, I suppose. But I tend to think that the ability to make logical conclusions is the evolved physical behavior of animal brains. That aspect of Whitehead and Russell’s Principia Mathematica and Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason are physically wired in our brains as are also the Lie groups that have evolved between the rods and cones of our eyes and the synapses of our neurons by virtue of which all living things have established that there is indeed a world out there to be worried about and to exploit.

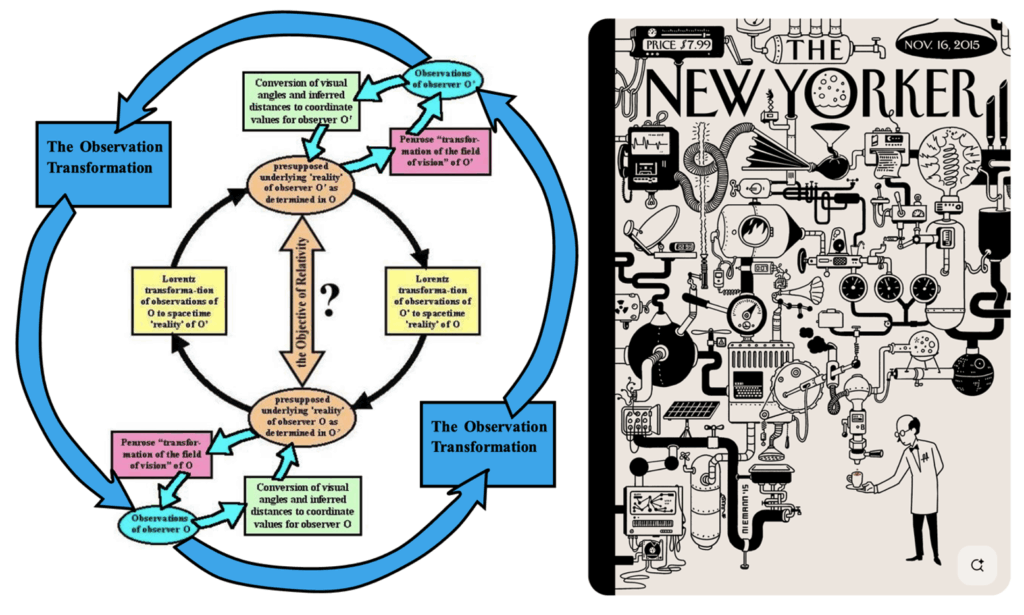

So we have this evolved capability of letting no opaque geode go unexamined. And, therefore, the quality of its explanation is subject to scrutiny. William of Ockham defined a valid criterion for determining whether an explanation of phenomena should be accepted. We can compare the quality of explanations put forward by Aristarchus and Copernicus and buy the explanation that’s the cheapest and the best, i.e., the simplest. To a lesser but necessary extent, we need to do that with every proposition. Perhaps even the Einstein/Penrose explanation of relativity; there is a simple formulation. And who needs a Platonic bubble filled with Rube Goldberg explanations.

Leave a Reply