Our familiarity with the concept of dimensions is based on a commonsense notion of specifying the locations of objects in what we otherwise consider to be an empty ‘space’. This involves the assignment of a triad involving ‘mutually orthogonal directions’ together with three real values along each direction respectively. Familiarity again suggested triads such as Forward, Left, Up; or North, East, Down; etc. In our equations we usually denote these as x, y, z or r, theta, phi depending on the coordinate system we choose. And that pretty much defines what we mean by the three dimensions of the space of our mundane reality.

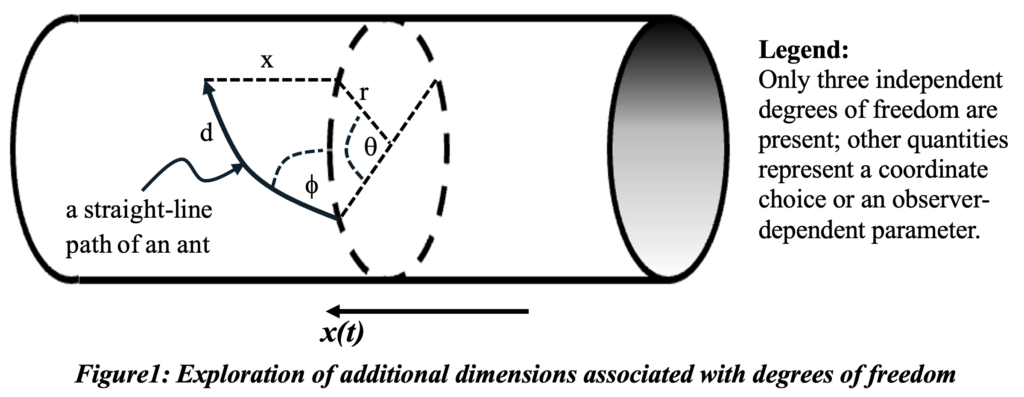

It is difficult to visualize (as against merely conjecture) more dimensions than these usual three that involve everyday experience. But in the book The Elegant Universe an excellent illustration and discussion was provided that involved an ant walking on a cylindrical hose in the context of explaining additional ‘curled up’ dimensions string theorists posit.[1] If the ant wishes to proceed along the general direction of the tube, its motion is constrained to the surface of the hose. While the axial direction of advance is fixed, he possesses an additional degree of freedom associated with motion around the circumference. The ant’s position is therefore conveniently described using cylindrical coordinates, with the fixed radius r, an angular coordinate theta, and usual axial coordinate along the tube, as illustrated in Figure 1.

If progress along some general direction (say a positive x axis) were to be constrained by some distortion of reality imposed by the value of r to include excursions involving additional degrees of freedom, it would be presumptuous to deny that each additional degree of freedom constitutes an additional dimension. But it would not be quibbling to ask how much further the ant must walk to proceed down the tube a distance x, even if the cylindrical surface were just a wire.

If r equals a fixed value greater than zero, phi equals a constant value between zero and 90° and if theta = theta(t), a continuous function of time, the path will be a perfect helix that cycles around the cylinder.

Our sense of both direction and distance in space as well as temporal relations of a traditional fourth dimension are all intimately tied up with our understanding of the propagation of light. This has been elaborated under the rubrics of electromagnetic theory, absorption theory, the special theory of relativity, quantum theory, and the general theory of relativity. So naturally what is meant by the legitimate degrees of freedom and dimensionality in general involves the modus operandi of photons rather than ants. With that in mind one must consider aspects of these theories rather than entomology to clarify what is meant by the ‘dimensions’ of space.

There are four electromagnetic vector fields identified by Clerk Maxwell, two electric and two magnetic. These are separated into E and B, which are referred to as ‘microscopic’ fields, and two, D and H that are referred to as ‘macroscopic’. Each pair is related to the other by properties of space. Microscopic fields are involved in emission, macroscopic fields with absorption and scattering. Thus, transmission (emphasizing the ‘trans’ as involving the emission as well as the absorption of light), i.e., both microscopic and macroscopic fields are involved. But emphasis on absorption came later. The energy density E of radiation involves all four of the electromagnetic fields, two associated with emission and two with absorption as follows:

where D is the electric induction field associated with absorption as defined by Maxwell, and B the magnetic field associated with emission. The symbol ‘•’ indicates that the ‘dot’ or ‘inner’ product of two vectors is to be taken, where X • Y = XY cos alpha, where alpha is the angle between the vectors.

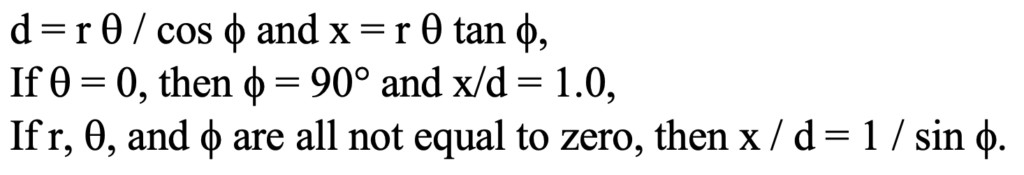

Light is a ‘transverse’ wave phenomenon, meaning that the waves of electric and magnetic fields crest in a direction orthogonal to the direction of the wave propagation. In addition, the electric and magnetic fields are orthogonal to each other. Momentum associated with these propagating electromagnetic fields (light) can be characterized by a Poynting pseudo vector P that is across product involving the microscopic electric field E associated with the emitter and a macroscopic magnetic field H associated with the absorber of the radiation.

The cross-product X ´ Y = u XY sin alpha, where u is a unit vector perpendicular to the plane that contains both the vectors X and Y and alpha is the angle between the two vectors.

However, B is often used rather than H to imply ‘emission’, ignoring the role of absorption in as much as H = B is generally assumed for a vacuum with no relative motion of the emitter and the absorber. This is shown in figure 2.

The three vector fields associated with propagating wave functions are mutually orthogonal like basis vectors in cartesian coordinates or in a coordinate frame North-East-Down. If one is tipped through an angle, another will be as well and that will define the direction of propagation.

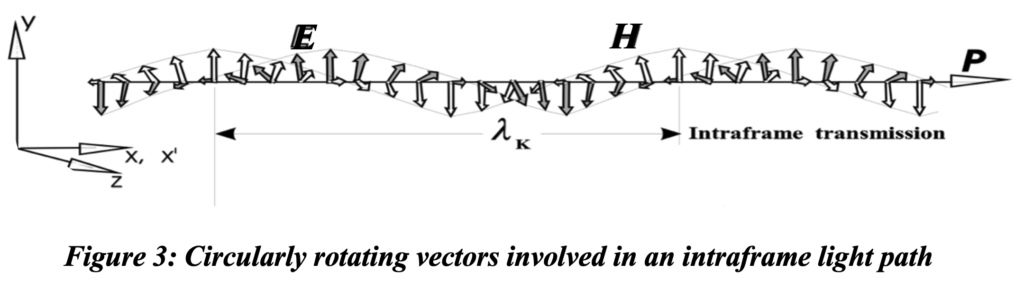

A circular oscillation of the electric field induces similar but out of phase and perpendicular oscillations of the magnetic field. When there is no relative motion between the emitter and absorber (intraframe transmission) the transverse wave that is circularly polarized in the most general solution to Maxwell’s equations, proceeds directly along the line-of-sight direction of the Poynting vector between the two interacting atoms. This is shown in the diagram of figure 3; either field (E or H) is very much like the ‘hand of a stopwatch traveling with the photon on a perfectly straight path as described so admirably by Feynman in his fascinating treatment in his QED.[2] This is just how light works as a transverse electromagnetic wave function.

Gilbert Lewis[3] insisted that light can not be understood as independently propagating through space following emission, but as a physical process jointly involving an emitting and absorbing system committed to an exchange of energy. In seminal papers published in the 1940s, Wheeler and Feynman4 elaborated earlier intuitions of Schwarzschild, Ritz, Tetrode, Lewis, and others [4] concerning various electromagnetic absorption theories. Later (in the 1980s) Cramer[5] introduced a commensurable Transaction Interpretation of quantum mechanics. With such an extensive background of serious work, it should hardly be considered a wild speculation to suggest at this juncture that fields from both an emitting and an absorbing atom might contribute equally to the energy and momentum of photons that facilitate transmission of energy and momentum between atoms.

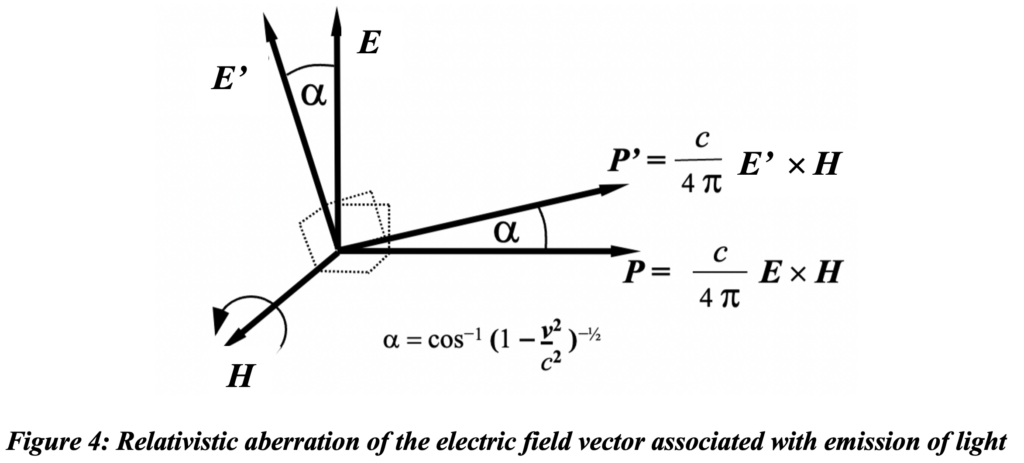

However, relative motion of interacting atoms substantially alters the momentum and energy transfer of the transaction. Let us consider how this classical (and even quantum mechanical) picture of transverse wave propagation is altered by the relativistic aberration formula in cases where the emitter and absorber experience uniform relative motion. The absorber of light is, of course, the ‘observer’ in a relativistic scenario. And so it is the electric vector that experiences aberration from the observer’s perspective.

A reference frame fitted with three perpendicular ‘rods’ to represent the three-dimensional basis vector directions are necessary for mensurable observations. These are typically shown as three arrows as at left in figure 3 with the unprimed labels x, y, and z. A reference frame of a second observer moving relative to the first along mutually aligned x and x’ axes have been assumed to affect only the x dimension of locations of mutually observed events. But that assumption does not take into effect the effects of aberration on observable phenomena.

In the frame of reference of the emitter the electric field is aligned at 90° to the line of relative motion and along a direction toward one or another star, but in the frame of reference of the observer (at the location of the emitter) the direction to that star and the emitters electric field is pointing at a direction that is off by the angle whose sine is beta = v/c, where v is their relative velocity and c is the universal speed of light in a vacuum. And therefore the emitter’s y’ and z’ axes would appear tipped relative to the absorber’s axes. Any direction perpendicular to a shared direction of relative motion in one frame of reference will appear to be at an angle for the other. (See the orientation E’ vector perpendicular the H vector in the absorber’s frame of reference in figure 4 for an illustration of this aberration effect.) Whether an electromagnetic field vector aligned with the y-axis in the unprimed system would be tipped in actuality rather than just appear to have been tipped for an observer is not a scientifically justified question.

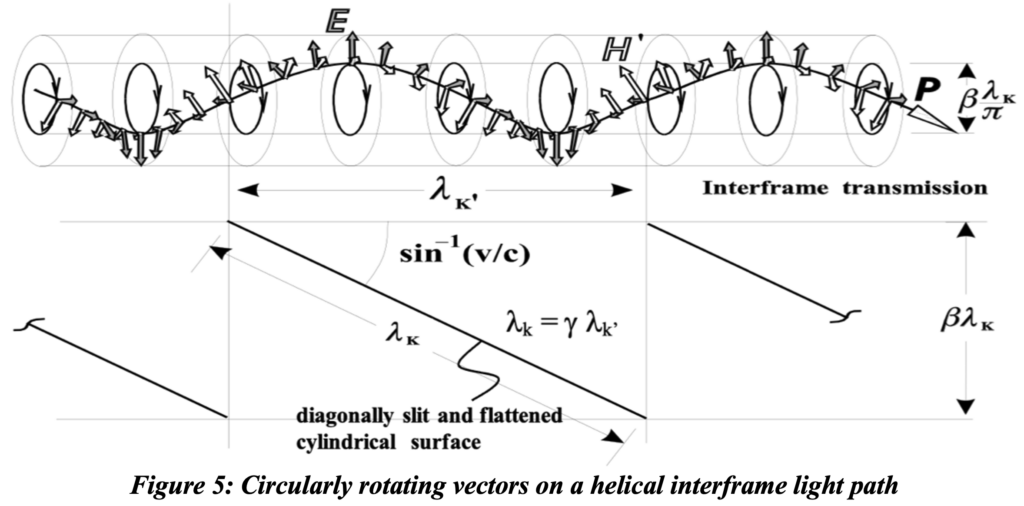

Now consider the directional relationships of E’ and H field vectors associated respectively with an emitter and absorber in different reference frames with shared x-axes as would two relatively moving observers. For propagation of light from the emitter to the absorber, these vectors will be tipped with respect to corresponding vectors in the other frame of reference, which of the vectors appear tipped depends on whether the emitter’s or the absorber’s frame of reference is considered the ‘other’. In figure 3 the emitter’s frame of reference was assumed for both the emitter and the absorber of the radiation, but when there is relative motion, the prime is used on E‘ associated with the emitter, which is therefore aberrated relative the H vector of the absorber, i. e., the E‘ vector will be tipped throughout the propagation. This tipping is conically symmetric throughout the entire circular polarization cycle, so the Poynting vector will follow a tangential path around the outside of a cylinder aligned with the common direction joining the centerlines of the emitter and absorber. This is shown in the interframe light propagation diagram of figure 5. Thus, when compared with radiation exchanged between atoms in a single frame of reference (intraframe transmission) there accrue appreciable differences in the propagation characteristic of radiation.

If the path of the ant in figure 1 were to maintain a constant angle f relative to the x axis it would be directly analogous to the path of light proceeding along the shared x axis from the emitter to the absorber of radiation. The velocity of light along its curved path would be c, but its velocity relative to the spatial separation of the two would be less by a factor of the square root of ( 1 – beta-squared ). So the lineal velocity of the light relative to the emitter’sframe of reference is slower than c although this universal velocity does apply to the actual circuitous path of the radiation. The universal speed of light applies in both frames, but transmission time will be longer (dilated) on an interframe exchange:

This produces the same result as the Lorentz transformation equations on round trip travel times between frames. It is not that the other observer’s clocks run slower such that interactions within his frame of reference happen more slowly, but only that in interchanges between their frames of reference will be slower than if they were stationary with respect to each other. There seems to have always been some confusion whether the differences are between the operation of clocks or time itself – and the same regarding rulers and spatial length. This is not the issue of quantum effects of measurement affecting what is measured; it is simply a linguistic issue needing to be discussed.

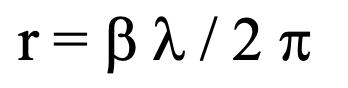

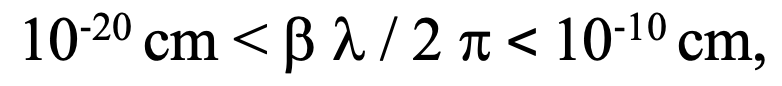

We spoke earlier of the ant having two extra degrees of freedom besides the x axis. So what are the similarities and differences in those degrees of freedom possessed by a photon of light? The radial dimension of the curvature of the ‘curled up’ surface surrounding a single coordinate is extremely small:

For usual wavelengths and relative velocities in our world, we have that:

where beta is the relative velocity in units of c, i.e., v/c. The wavelength of emitted radiation is lambda.

Thus, ‘curled up’ dimensions provide an accurate description of the physical phenomena that one encounters in dealing with uniform relative motion that has previously been assumed to map all of spacetime rather than all of the separately impacting individual transactions through space. String theorists suggest that the unification of the electromagnetic, weak, and strong nuclear forces are more effectively addressed in a mathematical framework of nine spatial dimensions, where only three of them are ‘observable’. Adding ‘time’ makes ten. They have assumed that the remaining two dimensions per spatial dimension are tightly ‘curled up’, which as we have shown, they are indeed.

Detailed description of the transit of photons of light – and not just ants –require more than one straight line direction projected on three dimensions to describe their meandering. Preeminent use of radiation in measurements made by instruments as well as our eyes recommend adopting the additional dimensions. But even more significantly, our epistemological understanding of time and space must surely lend significance to this curled up dimensionality.

This multidimensionality, arising from the transverse nature of light transmission when relativistic aberration is taken into account, provides a physical explanation for why Lorentz contraction and time dilation appear in situations involving relative motion. These effects, however, do not represent intrinsic distortions of physical objects or clocks. Rather, they arise from the geometric structure of light-mediated transactions between relatively moving observers. The differences between “this” and the “other” observer apply exclusively to situations involving relative motion between the systems participating in emission and absorption events. In this view, the ostensible distortions of length and time are not properties of the other observer’s clocks and rulers, but features of interframe communication, with aberration emerging as the primary observable consequence of relativity.

The wavelength and associated frequency of light are relational, not intrinsic to the helical structure of the transaction. Within this framework, Doppler shift is not a change in the frequency of the structure itself, but a reparameterization of phase along the geometric structure shared by emitter and absorber.

In a gravitational field, the geometry of light-mediated transactions may be continuously deformed, producing effects conventionally attributed to spacetime curvature. Such considerations suggest that the internal radius associated with photon propagation need not remain fixed. A full treatment of gravitational effects within this framework lies beyond the scope of the present work and will be addressed separately.

Spacetime geometry is inferred from light transactions; therefore, features traditionally attributed to spacetime may more properly belong to light. If light is—as it demonstrably is—the primary mediator of all measurement, then the geometry we attribute to spacetime may be nothing more, and nothing less, than the geometry of light’s transactions between relatively moving systems.

Leave a Reply