Subsequent to Einstein’s presentation of his theory over a century ago, a certain amount of dogma has accreted to it including a strange and quite inappropriate redefinition of observation peculiar to the discipline of relativity. I quote Shutz (1988, page 4) here:

“It is important to realize that an ‘observer’ is in fact a huge information-gathering system, not simply one man with binoculars. In fact, we shall remove the human element entirely from our definition, and say that an inertial observer is simply a coordinate system for spacetime, which makes an observation simply by recording the location (x,y,z) and time (t) of any event.”

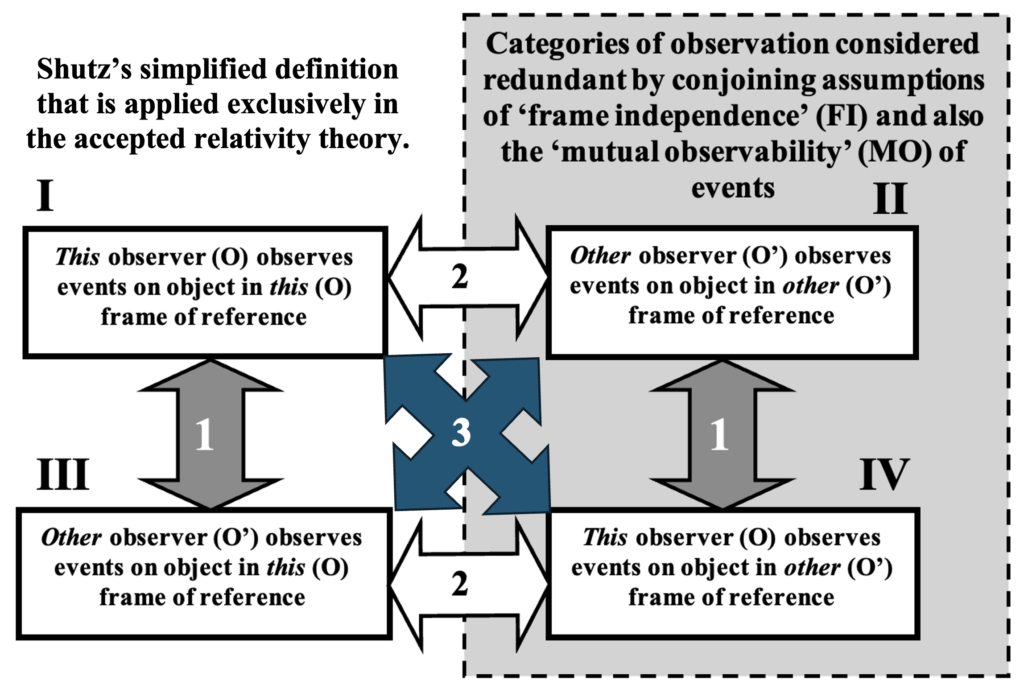

This definition is seriously flawed in precluding significant experimental evidence of differences observed by relatively moving observers. It indicates that the relationship is exclusively between the following observation categories:

A: Observations made by Observer O of events that take place on a mutually observed object

B: Observations made by Observer O’ of events that take place on a mutually observed object

Events are not butterflies in and of themselves. They are directly associated with and take place on some object and if that object is stationary within the grid of one of the observers it will (or at least one must prove that it won’t) be observed differently than if it were on something stationary within the grid of the other as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Four categories of observations and their amenability to experimental test

It is clear that Shutz had grouped observation categories I and IV, labeled as A, with II and III labeled as B. But all four categories of observation need to be compared experimentally in a conscionable effort to refute one’s conjectures. This was demonstrated in the discussion of frame independence (FI) and mutual observability (MO) in a previous post. There are three distinct comparison types indicated by the arrows labeled 1, 2, and 3 in the diagram of figure 1.

Type 1 are the traditionally considered relativity relationships. One would think that the type 2 relationship is trivial with no required consideration of relative motion even being involved unless the ‘other’ observer’s being in motion relative to ‘this’ observer makes his own internal observations suspect. Legitimacy of type 3 relationships are impugned by Shutz’s redefinition of observation, but they are the most essential experimental observations in exploring conjectured assumptions of the adequacy of his definition. Those are the observations that test to whether special contraction and time dilation are observable realities.

Addressing all four of the observation categories eliminates the simplification of using a one-to-one transformation between two illegitimately grouped observation categories. Instead, there are two types of each of the categories traditionally addressed. It is this distinction that ultimately precludes the deterministic transformation of observed events by one observer to what would be observed by another. Later posts will address the non-determinism of observational relativity.

Leave a Reply