Science is taught like world history with special deference to the winners of major disputes independent of the retrospective merits of either side. Unlike history, however, science can and must eventually alter mistaken decisions made in the past. Students of a scientific discipline are sometimes confused about why the original investigators made this assumption rather than that one or accepted one constraint rather than another. ‘Validation’ by instrumental success causes doubts to dissipate. By accepting legitimacy of decisions made at every juncture, the student eventually understands all the mechanisms and becomes adept at applying the resulting theory. He or she comes to believe that there was no other viable approach to solving those problems.

The concept of ‘dark matter’ was introduced to satisfy the perceived need of more mass to account for what were apparently gravitational effects. The hope was and has been that someday it would be determined what exactly it is, whether it is hot or cold, etc. A consensus is that it must be cold, with no radiation emission or absorption, i.e., thermodynamically inactive. Graduate students who had begun publishing as members of long lists of contributors, became recognized professors and headlined publications.

But unanswered questions persist; what if one had taken another path, leaving a different question unanswered. What if one had persisted in considering previously rejected assumptions, might one in retrospect have come up with a better theory in which dark matter and whether it was hot or cold were totally irrelevant? What if the observed phenomena is not even gravitational. In world history genocide by ‘winners’ precludes a going back. But science is different – it should be different. Shouldn’t it? At what point should one cease to challenge an accepted but incomplete and inconsistent theoretical notion, a year, a decade, a century. What is the ‘use-by’ date for unanswered, even if unasked, questions?

Here we are, well on in the twenty first century still wondering what ‘dark matter’ is – a century after its introduction and continued instrumental success. Is it too late to acknowledge that words matter – even, and especially, to scientists? They direct our thoughts, constrain our concepts, determine what we look for, and how we look for it. Beside their denotations words carry with them an aura of connotations. It is confusing when what we seek is given a misleading adjective such as ‘dark’ that conjures aspects of the associated noun that do not apply, particularly when conjoining ‘dark’ with ‘matter’. But when something has been given a name, it would be doubly confusing to call it by another, so we’ll go with ‘dark matter’. But we should at least acknowledge that ‘it’ isn’t ‘dark’ and it isn’t ‘matter’ in any sense that had any meaning before the ‘it’ was given a denomination. Its origin is ‘missing matter’ and its essence is ‘invisibility’. ‘Missing’ implies correctly that it may not even exist, and ‘invisibility’ accommodates existence in only the vaguest of terms. Objectively, what we are dealing with are effects that are typically produced by traditional material substance, but in this case the perceived source is not observed.

The epistemic value of words is that they bring phenomena into existence in the sense of an awareness of their existence. Previously, stars and galaxies comprised of them had been more exclusively of interest to astronomers and cosmologists; a dearth of which required an alternative explanation of orbital effects of galaxies in clusters and rotation of stars in massive galaxies. In the background of all these astronomical investigations there was an increasing awareness that what we had observed of the universe in visible light was only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. So dark matter took center stage. The greatly increased dispersion of redshift across galaxy clusters epitomizes what dark matter is assumed to have caused, but it is nothing more than obscure words for an undiscovered cause of a physical effect. Searching for attributes like hot or cold to associate with that name rather than details of the effect itself is a total misdirection of effort unbecoming a scientific discipline.

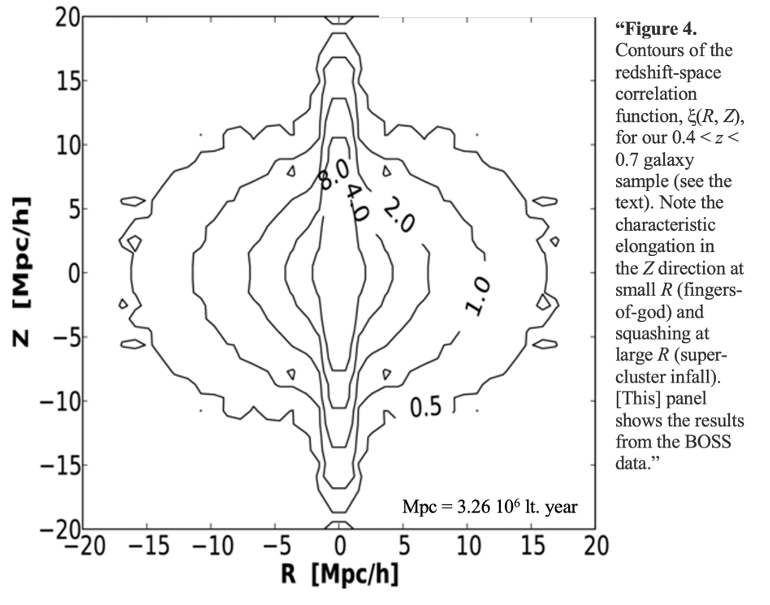

Rather than placing the emphasis of research on the nature of the presumed cause, which is dark matter by whatever name, we need to discover the precise nature of the effect which is redshift dispersion across galaxy clusters. This is not a major insight in as much as cause and effect – two ends of a syllogism – have become synonymous in the parlance of cosmology. This requires the quantification of redshift dispersion across the breadth of galaxy cluster domains and to determine its correlates with other physical aspects of clusters than just the virial theorem. The environs about a galaxy cluster including the sparse regions out to the borders of adjacent cluster cells has been given the name of ‘dark matter halos’, tying the effect ever closer to its presumed cause. A name such as ‘galaxy cluster cells’ or domains would have been preferable to ‘halos’ to associate with the ‘fingers of God’ phenomena just to avoid the transference we have addressed above. But a rose is a rose is arose I suppose and by any other name it smells as sweet as they say.

Research into the nature of the redshift that occurs in light passing through these domains has been addressed by Martin White, et al (2011) under the heading of ‘halo occupation modeling’ in a fine article that provides excellent data (even if unintended as the purpose) for investigating other possible causes of the effect. The figure below is taken from that article.

We will address the data in that reference and come to different conclusions in a subsequent post.

Leave a Reply